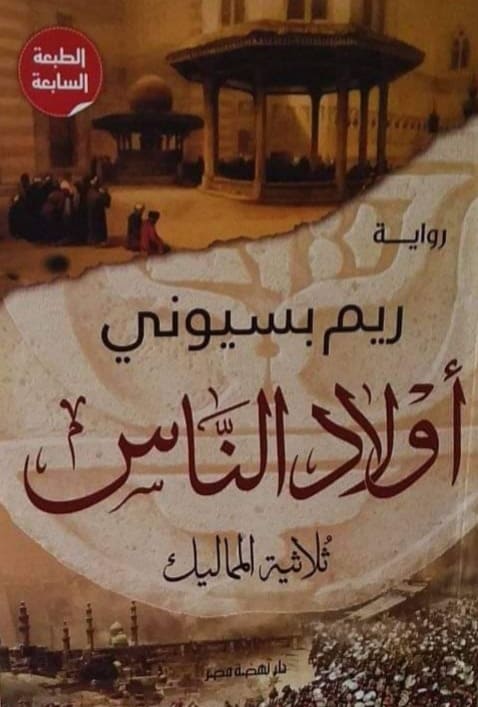

Mamluk Cairo Comes Alive in Bassiouney’s Trilogy

Dr. Reem Bassiouney’s latest work of fiction is a masterful, multi-generation epic set in Mamluk Cairo (1309-1517). The action moves out of Cairo at times, to Alexandria, Greater Syria, or the Western Desert, but it is focused around several historic buildings of Mamluk Cairo. There are also brief scenes from 2005-2017. For me, the heart of the book lies in the first of the three main stories, set in the 14th century.

The book contains three main tales: *Awlad al-Nas */ Children of the People, Qadi Qaws / A Qadi Named Qaws, and Hadithat al-Layali / Nocturnal Mishaps. Together they combine Bassiouney’s careful historical research with the finesse of a talented storyteller. The first section is named for Awlad al-nas, a name used in 14th-c. Egypt to refer to the children of Mamluk rulers. While Mamluks were born in Anatolia and imported to Egypt, their children were born in Egypt and were known as ‘children of the people.’ Often these children’s parents were not from Egypt, although in some cases, one of the parents was Egyptian. The identity of the children resulting from these unions was open to speculation, depending on the social climate.

The story Awlad al-Nas tells a tale of a Mamluk ruler who chooses a bride from a middle-class Egyptian family. It is the first in a series of unusual choices he makes. Together this couple affects the fate of their country and they leave their mark on history. Their names are inscribed in the Cairo mosque of Muhammad b. Abdullah al-Muhsini where they were entombed with their loved ones. This opening tale of love and adventure, for me, was the most thrilling part of the trilogy. The characters are believable, their dialogue both meaningful and natural. The story pulls the reader along with surprises and a clear narrative arc. It also examines and reimagines the experiences of boys who were captured and enlisted into Mamluk service and the ways that they were, and were not, integrated into society in Cairo.

After the couple’s death, there follows a tale of their creative son and his adventures. This section, beginning in 1353, is most significant, in my reading, for its representation of a historical period as well as a key theme of Bassiouney’s writing. This son is obsessed with architecture and the desire to design and build an architectural marvel. This theme appears in other work by Bassiouney (as in her novel Mortal Designs / Ashiya’ ra’i‘a), as well as others’ work, such as The Architect’s Apprentice by Elif Shafak. Characters in these works follow aspirations of art in order to fulfill their need to create, to memorialize their patrons, and to contribute to their civilization. This section considers the life of the artist. What responsibilities do artists have? How does creativity affect family life? How does it affect society?

Qadi Qaws / A Qadi Named Qaws opens in 1388 with a qadi (religious judge) named Qaws facing a time of tense power struggles between clerics and rulers in Mamluk Cairo. Bassiouney captures this internal strife in the Muslim establishment beautifully, showing what it must have felt like for ordinary Egyptians, complete with her sense of humor: “For the first time, the Coptic Christians and Jews looked at Muslims with eyes of pity and understanding. Their lot was certainly worse!” (p. 289, my translation). Three women come to visit the qadi, presenting two legal cases and requesting his intervention. These two cases will lead to horrors and delights for the unsuspecting qadi. The historic madrasa / school of the Sultan Hasan Mosque also appears in this story.

The Mamluk era comes to a close with the coming of the Ottomans in 1517. The final tale weaves together three eyewitness accounts of this tumultuous era (1517-1522) by: a woman named Hind, a man named Salar, and a scholar named Mustafa. This final tale includes the dark terror of this time, but like the others, it also tells a story of human endurance and the commitments that bring people together against the odds.

There is plenty of social diversity throughout the trilogy, touching on issues of racism (such as a preference for lighter skin or for Turkish instead of Arabic), interreligious tensions (both within a community and between communities), different religions (including a Christian character and some characters who do not necessarily practice any religion), and marginalization of women practicing “magic.” This last theme also appears in Bassiouney’s earlier work (Mortal Designs / Ashiya’ ra’i‘a). Each tale includes a love story, woven in amidst action, intrigue, suspense, and history. The last two pages of the book suggest that these stories of love are also stories of healing, offering hope, warmth and meaning in the lives of mortals consumed by daily toil and turmoil. The collection is characterized by a deep respect for spiritual life and values. It also asks questions about identity, responsibility, and what happens when people realize that their attitudes, ideas, or actions are no longer in alignment with their personal values. The history is meticulously researched by Bassiouney. This trilogy gives new life to historic Mamluk Cairo for all of us to learn from and enjoy.

Note: All images and review copy of the book provided by Reem Bassiouney. This review was written as an independent, honest review by Melanie Magidow. The trilogy is currently available in Arabic only. ArabLit Interview with Reem Bassiouney here. For Arabic video review by Nada El Shebrawy on her YouTube channel, Dodet Kotob, see the episode “المحتوى العربي على كيندل | How to Find Arabic Books on Kindle” here, from 6:00 to 10:00.