Juha’s Wife

*Using gender to define the core of what makes us human creates huge contradictions: it requires us to define men and women as fundamentally different from each other and yet also as full human beings. – *Johnson, The Gender Knot, 58

Just as women appear in limited and occasional historical events universally, so the popular Arab folktales of Juha the trickster portray his wife in a supporting and marginal role. If Juha were female, the stories would not have been so popular since social authorities would not relate to them. Nevertheless, Juha’s behavior does not always mirror established views on gender. Instead, tales of Juha can serve as a counter-voice to traditional patriarchy as they portray strong and independent women in Juha’s life. Juha stories are vehicles of humor, portraying multiple social voices.

Who is Juha? Through his speech and conduct, Juha has entertained generations of Arabic speakers and their neighbors. Tales of Juha grow out of a long cultural tradition of storytelling, steeped in the rich history of Western Asia and North Africa. Juha’s nationality, language, and religion, not to mention the form of his name, vary according to the storyteller. Juha appears in writings from the tenth century to today. He is a particularly flexible character—both young and old, foolish and wise, honest and dishonest, he is essentially human and represents the common person. People of every social class appear as characters in his stories, from the beggar to the king, and from the merchant to the imam.

Gender interactions in Juha stories occur largely within the family. The tensions and contradictions present in such interactions are generally not particular to the Arab-Islamic cultural context. In order to understand Juha’s relationship to women, we begin with a story that includes his mother. She generally appears in stories as a resourceful and patient woman who endures the antics of her unusual son. In December 2003, I traveled to Morocco for four weeks of gathering data from oral and written sources of Juha stories. I first heard The Bowl and the Oil on board a train to Fes. One of the two men sitting across from me in our private car began telling stories of Juha, and he included the following anecdote:

Juha’s mother asked him to get some oil, so he went out for oil and put the oil in a bowl, but there was a little left [i.e. wouldn’t fit in the bowl]. So he turned the bowl over, and put the rest on the bottom, carefully carrying it to his mother. When he arrived, she asked him, “Where is the oil?” He said, “Here!” And he turned over the bowl, but it was all gone!”

Juha follows his mother’s instructions without hesitation or argument, and he attempts to carry them out with precision and accuracy. His behavior indicates the mother’s authority. Is Juha’s mistake really unfortunate, accidental, or innocent? Perhaps the entertainment value comes in part from Juha’s successful foiling of his mother’s plan. One Moroccan, when asked whether or not Juha respected his parents, explained: “He’s often respectful of his parents, but if he wanted some money and his parents have some, he might steal the money from his parents—maybe—not stealing like a thief! But with cleverness—he could say to his father, ‘Daddy! Please give me a little money…’ this way.”[6] Like a Calvin and Hobbes comic strip, this anecdote presents the trickster character as a boy frustrating his mother’s good intentions with the aim of amusing the audience.

In some Juha traditions, such as Jewish and Sicilian folktales, the mother’s frequent presence may indicate that Juha lives with his mother long after his childhood. Despite the question of his age, the mother is certainly a more prominent character than the father in Juha stories throughout the world. Why isn’t Juha’s father present? After making the above, hypothetical reference to Juha’s father, I.B. explained, “I personally say that he has no father. Why? Because the child who has a father won’t be Juha.” For this man, who is a father, Juha must struggle with the challenges of a broken home. He does not seem to come from a strong and supportive family because he resorts to trickery and can be insensitive or cruel. Of course this man considers the father essential to the proper upbringing of a boy who will grow into a respectable, upstanding citizen. Patriarchal values survive through consistent role modeling and transmission from father to son. But Juha questions and challenges traditional models through passive resistance.

Most Moroccan women who I interviewed responded to the question of Juha’s respect for his parents positively, affirming his general kindness and pointing out that they themselves remember stories of Juha from their mothers and tell them to their own children. No female respondent raised the issue of gender inequality directly or found Juha stories offensive. Perhaps stories such as the Pregnant Bride story cycle help explain why women are supportive of Juha stories. The following stories present Juha’s recent bride giving birth:

Born in Three Months

Juha married a beautiful woman, and she gave birth after three months. So the women gathered to name the boy, and each one chose a name. Juha was standing nearby, and he said: “The best name for him is Speedy!” So they asked, “Why is that, Juha?” He said, “Because he cut an interval of nine months into three months!”

Born in Five Days

Juha married a woman, and on the fifth day of her wedding celebration, she bore a son. So Juha went to the market and bought a slate and ink. And they said, “What’s this?” And Juha said, “[The one] who is born in five days goes to school in three days!”

The lack of his bride’s virginity does not disturb Juha or disrupt his plans to raise a child in a supportive family. Instead, he finds an alternative explanation for the unorthodox state of affairs. Though his reasoning seems faulty and naïve, his intentions are still honorable. His provision for his bride’s child resists the powerful social ideal of bridal virginity in the anonymous form of a popular joke. His marriage is not built upon fidelity as much as it consists of guileless commitment to the marriage.

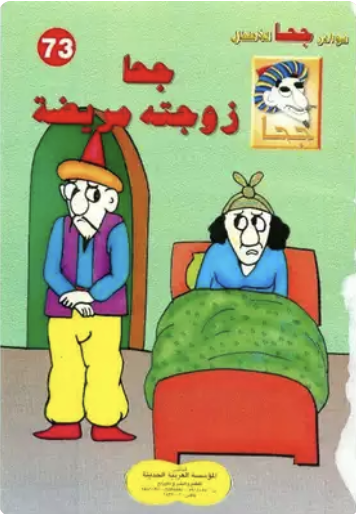

Like her husband, Juha’s wife is a fairly flexible character. Traditionally, she is responsible, capable, and attentive to her husband’s needs. Sometimes she is a helpful, caring woman; more often she is fierce, or even spiteful. A subset of stories involving Juha’s wife portray Juha’s bride, as in the above stories, as unchaste or ugly and yet able to manipulate Juha into marriage. Though the wife is often a strong woman, I know of no story in which she appears without Juha. Similarly, Juha never appears in a romantic relationship with any other woman. His relationship with his wife generally points to tensions in marriages, expressing people’s anxieties, concerns, and frustrations with patriarchy through story.

In the following story, Juha’s wife behaves as a strong and independent woman. Juha’s behavior radically departs from patriarchal assumptions of men’s authority and control over women’s sexuality:

Do You Want Him to Go Away More?

Juha’s wife got mad one day, and she said to him: “Go away from me.” So he put on his shoes, left the house, and walked a long distance until he reached the end of the town. [There] he came upon his neighbor on a donkey. So Juha said to him, “If you get home, God willing, ask my wife, ‘Do you want your husband to go away from you any farther?’”

Similar to Juha’s mother, his wife directs him to leave the house. He obeys promptly, reversing the prevalent social ideology that women obey and submit to men. Then he sends his neighbor to his wife, despite the fact that she is alone. Usually, it is male neighbors who present the greatest threat to wives’ virginity, as demonstrated in the following widespread joke:

Certainly

Juha was asked, “Is it possible for a child to be born to a man whose age is more than one hundred years if he should marry a young woman?” Juha said, “Certainly, if he has a neighbor in his twenties or thirties.”

In the following anecdote, a fire breaks out. In patriarchal societies, the archetypal fire fighter is a man. Men assume responsibility for their families and homes. When the house is in danger or comes under attack, it is they who must act by default. Juha’s response in the following story serves as a challenge to widespread social ideology despite its continued representation of separate gender roles:

Minister of the Interior

One day a fire broke out in Juha’s house. One of his neighbors came and told him, “Your house is on fire! I knocked on the door a lot, but no one came.” Juha answered coolly, “My brother, I have split the responsibilities between myself and my wife into two divisions: for me, the outside work, and for her, all matters of the house. So go tell her about the fire—she is Minister of Interior Affairs.”

Evidently Juha’s marriage does not rest upon physical strength. Instead, the division of labor lies in location and not in the degree of physical exertion or the intrinsic value of the activity. Juha displays complete confidence in his wife’s capabilities, baffling his neighbor with his own indifference to this opportunity to prove himself as protector of his household. He’s not interested in doing any extra work (hence the humor), but he’s also not identifying as a member of the dominating, male majority.

Part of the humor value in stories of Juha’s strong wife lies in the common expectation that men be heroic and dominant. When Juha behaves ignorantly, naively, or childishly, the stories call into question the patriarchal notion of male authority. The counter-voice of Juha stories provides an important, more honest alternative to the typical images of men as independent and invulnerable. Portraying Juha’s wife as more capable and responsible than her husband playfully ridicules the expectation that men hold authority simply because they are men.

Despite the strength of Juha’s wife, she remains a marginal figure in the genre of Juha stories. As a result of patriarchy, the character who best represents humanity in popular jokes is most often male. However, Juha does not fulfill patriarchal ideals. He resists the dominant ideology by mirroring the tensions and contradictions inherent in patriarchal society.

Notes

If you’re interested in reading a collection of Juha stories in English, I recommend Interlink’s Tales of Juha (Amazon link here).

For a written version of “The Bowl and the Oil,” see Dov Noy, Moroccan Jewish Folktales (New York: Herzl Press, 1966), 52.

All interview references (except the one on the train) were from Fes on December 26, 2003.

Source for “Born in Three Months”: Imilīn Nasīb, Nawādir JuHā wa-Ashʿab wa-Ṭarāʿifuhumā (Beirut: Dār al-ʿilm li’l-Mulāyīn, 1994), 41. My translation.

Source for “Born in Five Days”: Nawādir, 41. My translation.

Source for “Do You Want Him to Go Away More?”: Nawādir, 45. My translation.

Source for “Certainly”: Nawādir, 94. My translation.

Source for “Minister of the Interior”: Nawādir, 48. My translation.

Image Sources: Juha and Donkey | Juha and His Sick Wife