Listening to Popular North African Voices of the Early 20th Century

I grew up surrounded by memories of WWII—not my own of course, since it officially ended more than 30 years before I was born. My grandparents’ military service was common knowledge among those who knew them. Films like Casablanca and War and Remembrance were familiar. In school, we studied Holocaust accounts.

Later, when I lived in Morocco and Egypt, I found a disconnect between the WWII memories that are circulated in the US and the lived experiences of the peoples of North Africa. The problem I see is the total erasure of the local population in portrayals of North Africa during this period. For example, from the famous film Casablanca (1942) to The Netflix series El tiempo entre costuras/*The Time in Between *(2013-2014), which took place mostly in “Tangier,” there are no Moroccan characters. Where are the films, books, or other documents to fill in the picture? This yawning silence prompted me to learn more.

I discovered Revisionary Social History in college, and was fascinated by attempts to incorporate marginal voices into historical studies, outside of the history told by conquerors, focusing on those with wealth and power. Even with my limited student budget, I bought Goitein’s multi-volume A Mediterranean Society, in which he mines the Geniza for information about the lived experience of communities scattered throughout many countries, at various socioeconomic levels. The focus is on Jewish lives in the 10th-13th centuries in the Mediterranean region. Amitav Ghosh’s In an Antique Land also made an impression on me.

More than a decade later, I find that my scholarly work (research and translation) addresses the gaps I found between historical representations of North Africa, devoid of any local voices, and the voices that are still present in folk literature. My translation of *Sirat al-Amira *(The Tale of Princess Fatima, see here) does not include voices from North Africa in the early 20th century, but it does reveal a story collection that was enjoyed widely during that time. (For an example of how popular epics impacted people in North Africa in the 20th century, see Rachel Schine’s article on Judeo-Arabic epics here). My current project, translating the first anthology of Moroccan Malhun poetry to English, includes art that was composed and performed by and for audiences in North Africa throughout the 20th century (and earlier and to this day).

My work brings to light the diversity in historical societies of North Africa: gender dynamics (especially in Sirat al-Amira), religious communities (in Jewish and Muslim Malhun poetry, for example), and multiple languages and cultural influences (in Berber folktales and Juha stories, which I wrote about earlier). It is gratifying to contribute to a more inclusive and democratic society, and a world in which we listen to one another and consider multiple perspectives.

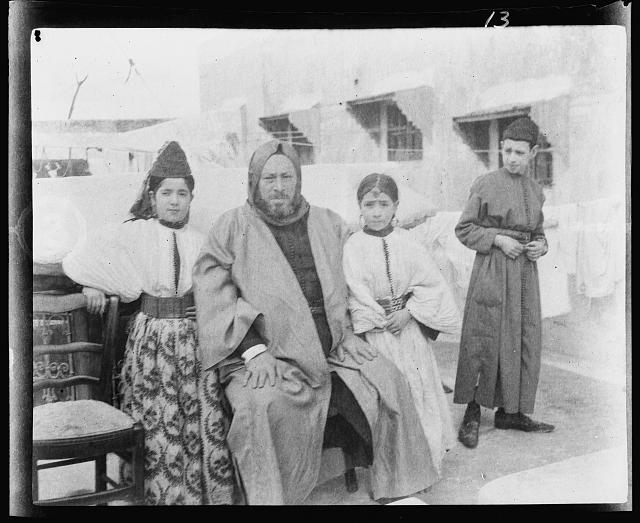

Image sources: