Poem: Ibn Arabi, Love, and Resilience

This month we have a Sufi love poem by Ibn Arabi, a chance to rest from your tasks and worries. This poem contains some of the most-quoted lines of poetry in Sufism and in anthologies of pre-modern Arabic literature. Usually only a few lines are included, as in these two examples:

My heart is capable of every form:

Pasture for deer, a monastery for monks,

Temple for idols, pigrim’s Ka’bah,

Tables of Torah and book of Qur’an.

My religion is love’s religion: where turn

Her camels, that religion my religion is, my faith.

— Ibn al-ʿArabi (1165–1240), in Robert Irwin, Night and Horses and the Desert (New York: Random House, 1999, 298)

There was a time when I took it amiss in my companion if his religion was not near to mine;

But now my heart takes on every form; it is a pasture for gazelles, a monastery for monks,

A temple for the tables of the Torah, a Ka’bah for pilgrims and the holy book of the Quran.

Love is my religion, and whichever way its riding beasts turn, that way lies my religion and belief.

— Quoting Sheikh Muhyiddin Ibn al-ʿArabi in Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, What’s Right with Islam: A New Vision for Muslims and the West (New York: HarperOne, 2004, 284)

You can view the full poem, with a beautiful English translation by Michael Sells, in the PDF handout I created here. It is also available online here.

Commentary

In his notes, Michael Sells points out the four themes in this poem:

- Nasib: Remembrance of the beloved, especially the departure of the beloved from a shared campsite

Sufi concept of fanaʾ or union with the beloved through the passing away of the ego self

Hajj: pilgrimage and circling the Kaaba

Sufi idea that the greatest Kaaba is the heart of the divine lover during fanaʾ

You can enjoy the poem for its nature imagery and expressions of love and acceptance alone. Or you can seek a deeper understanding of the poem. Michael Sells raises the question: “Why would Ibn Arabi evoke the mournful cooing of the doves…and the movement of the beloved…AWAY from the poet?” He responds: “The heart that is receptive of every form must be willing to give up each image, each form, each beloved, in order to be receptive for the next form.” He terms this a “mysticism of perpetual transformation, taqallub (a play on the word heart, qalb).” I would add that this is a practice of a kind of resilience, a recognition that change is always taking place. Even as the heart holds a person, situation, or idea dear, it also has the capacity to expand beyond that which is held dear. As we’re reminded at the end of the poem, all those lovers who have gone before us are reminders that we too are capable of rich experiences, with all its fireworks and heartaches. I find myself encouraged to meet all those “feels” of the human experience, trusting that the heart is big enough to meet them and strong enough to continue on the path of life.

Who Was Ibn Arabi?

Ibn Arabi was an influential Andalusi Arab scholar and mystic who lived in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. He was born in Andalusia (today Spain) and died in Damascus, having traveled widely throughout the Muslim world of his time. He produced hundreds of works and is best known for his Sufi poetry and philosophy. The poem included here is the eleventh in his collection of mystical love poetry called Tarjuman al-Ashwaq (Translator of Desires). It was inspired by Ibn Arabi’s love for a woman he met in Mecca in 1204. Michael Sells calls this poem “the keystone of the Tarjuman.”

What Is Sufism?

Sufism is a branch of Islam, originating from its earliest days in seventh-century Arabia. It continues to this day in a plethora of tariqas or orders. Sufism is not a sect or denomination so much as an approach to religion, focusing on the meaning of practice and on connecting to the Divine. Like all Sufis, Ibn Arabi was inspired by an experimental and symbolic religiosity.

Why Does this Matter Today?

Most industries are in a state of transition following the global pandemic and there are painful current events, not to mention the environmental crisis. It’s an excellent time to read a poem celebrating beauty, tolerance, love, yearning, and devotion!

In the spirit of making room for change, here is a more disruptive rendering by Robin Moger of those famous lines quoted above:

Walled in fires, the shape of my heart unstabled

Becomes a pasture for gazelles, a house of monks, of idols,

A Kaaba to turn about, a Torah’s turning leaves, Quran.

Take love.

Where its caravans drive

Is faith.

— Yasmine Seale and Robin Moger, Agitated Air: Poems after Ibn Arabi (London: Tenement Press, 2022), 79

Translation and re-translation is re-thinking. Running our ideas through languages allows us to view a reality over again, to shift our perspective and open new space for new realities.

Sources

Ronald Nettler, “Ibn al-ʿArabi,” in The Routledge Encylopedia of Arabic Literature, ed. Julie Scott Meisami and Paul Starkey (New York: Routledge, 2010), 311–12.

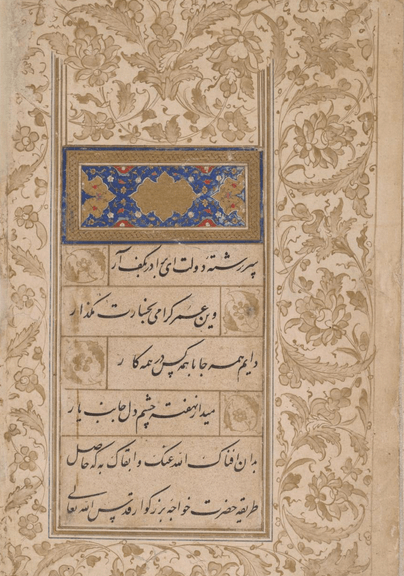

**Images: **1) Unnamed Sufi Treatise, Library of Congress (Link); 2) Iskandar on pilgrimage at the door of the Kaaba in Mecca, Harbard Fine Arts Library (Link); 3) Leaves by Chris Lawton, Unsplash (Link); 4) Shrine of Ibn Arabi in Damascus (Link); 5) Portrait of a Sufi, Harvard Fine Arts Library (Link).